Countess Marianne von der Leyen

Born as Maria Anna Helene Josephina Freiin von Dalberg on March 31 1745, she was the

daughter of Franz Heinrich von Dalberg and Countess María Sophia von Eltz-Kempenich, born in

Mainz.

On the occasion of the imperial election in 1765, she was in Frankfurt at that time and there she met her future husband Franz Georg Karl Anton von der Leyen. They married in the same year and, according to tradition, moved to the family residence in Koblenz. Over the next three years, their family grew to include three children, the heir count Philipp and the two younger daughters Charlotte and Maria.

They lived in the Von der Leyen residence in Koblenz until 1773, when they moved to the castle in Blieskastel. During his reign, Count Franz Karl's goal had been to improve the region economically and socially, but he died of blood poisoning in 1775. Widowed, Marianne von der Leyen took over the regency as guardian of her nine-year-old son at the age of thirty and held it for eighteen years.

On the occasion of the imperial election in 1765, she was in Frankfurt at that time and there she met her future husband Franz Georg Karl Anton von der Leyen. They married in the same year and, according to tradition, moved to the family residence in Koblenz. Over the next three years, their family grew to include three children, the heir count Philipp and the two younger daughters Charlotte and Maria.

They lived in the Von der Leyen residence in Koblenz until 1773, when they moved to the castle in Blieskastel. During his reign, Count Franz Karl's goal had been to improve the region economically and socially, but he died of blood poisoning in 1775. Widowed, Marianne von der Leyen took over the regency as guardian of her nine-year-old son at the age of thirty and held it for eighteen years.

Of castles and chateaus

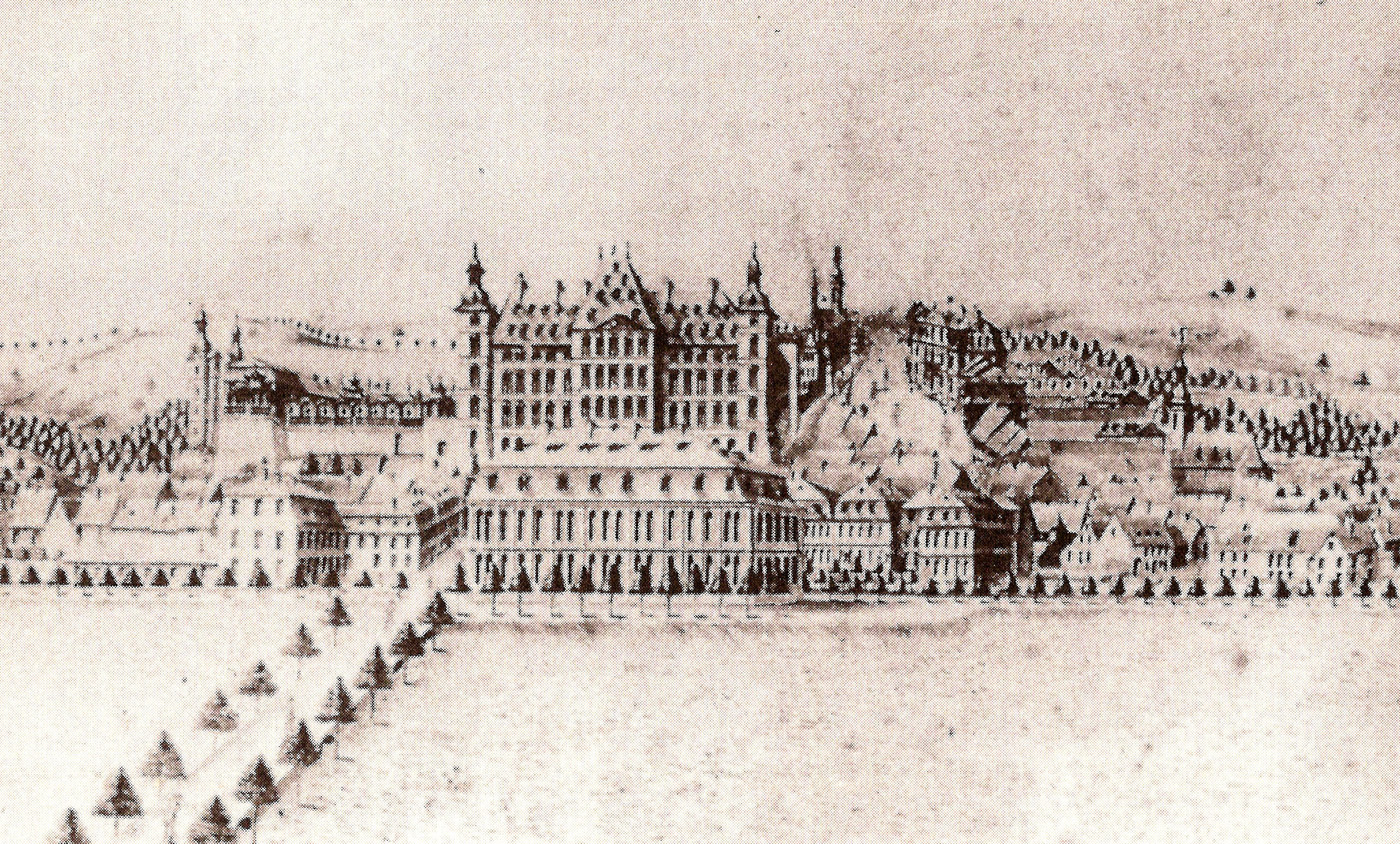

When the family moved to Blieskastel in 1773, a lively construction phase began. Count Franz Karl

created a large orphanage that also served administrative purposes and still functions as a town

hall today. Marianne von der Leyen also had several buildings constructed, including many castles

and country houses. The construction of the Blieskastel Castle Church was also commissioned by

the Count, but Marianne was the one who laid the foundation stone one year after his death.

Furthermore, she had a castle built in Rilchingen, which was intended to serve as her retirement home, as well as numerous pleasure buildings such as the Annahof or the “Rote Bau” (engl. “Red Building”), which have been preserved to this day. However, the castle in Rilchingen was destroyed by French troops before it could be used.

All these building projects put a financial strain on the region, but especially the magnificent construction of the Philippsburg, which her son Philipp had built, led the county into deep debt. As the French Revolution approached, the Countess gave up some of her buildings, including the Annahof and the Red Building, sparing them from the revolutionaries. In contrast, the magnificent Philippsburg was plundered and demolished by troops in 1793 until it was almost completely destroyed in the autumn.

Image: Philippsburg Castle (reconstruction) in Niederwürzbach Gerhard Philipp, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE.

Furthermore, she had a castle built in Rilchingen, which was intended to serve as her retirement home, as well as numerous pleasure buildings such as the Annahof or the “Rote Bau” (engl. “Red Building”), which have been preserved to this day. However, the castle in Rilchingen was destroyed by French troops before it could be used.

All these building projects put a financial strain on the region, but especially the magnificent construction of the Philippsburg, which her son Philipp had built, led the county into deep debt. As the French Revolution approached, the Countess gave up some of her buildings, including the Annahof and the Red Building, sparing them from the revolutionaries. In contrast, the magnificent Philippsburg was plundered and demolished by troops in 1793 until it was almost completely destroyed in the autumn.

Image: Philippsburg Castle (reconstruction) in Niederwürzbach Gerhard Philipp, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE.

Regency & Social Engagement

Due to the early death of her husband, Marianne von der Leyen took over the regency as

guardian for her son in 1775 and strove to continue her husband's goals by trying to further

develop her country economically. To achieve this, she introduced social and educational

measures by building orphanages and introducing mandatory education for elementary schools in

1775. In addition, she abolished serfdom in 1786 and established a widow and orphan fund.

The economic development was to be improved by promoting the development of agriculture, horticulture, and livestock breeding. She also supported the industrial sectors of mining, metallurgy, and glassmaking. She created jobs by establishing a factory for earthenware and a printing house, where the weekly newspaper was printed.

Although her son reached legal age at 25 years old in 1791, he showed no interest in the regency, so Marianne von der Leyen continued the regency until 1793.

The economic development was to be improved by promoting the development of agriculture, horticulture, and livestock breeding. She also supported the industrial sectors of mining, metallurgy, and glassmaking. She created jobs by establishing a factory for earthenware and a printing house, where the weekly newspaper was printed.

Although her son reached legal age at 25 years old in 1791, he showed no interest in the regency, so Marianne von der Leyen continued the regency until 1793.

click around to close

Emerging conflicts

Despite her efforts to improve the social situation in the region, this caused resentment among

the population. It was seen as interference from above, as she defined what the common good

was and how to improve the situation of the population. Many residents insisted on their old and

ancestral rights and did not see the changes as an improvement.

Moreover, the region fell into ever-deepening debt. The lavish wedding of the heir prince and the construction of the Philippsburg exacerbated the situation and placed greater burdens on the inhabitants.

In addition, disputes over forest and charcoal rights had existed since 1765, which reached their peak in the St. Ingbert forest dispute in 1789. The St. Ingbert commune sought support from other communities, and so 19 of the 38 communities in the region gathered for a meeting in which they collected their protest in 25 points of complaint. These were submitted to the Regent, where they found no hearing, so the protests continued.

In December, Marianne von der Leyen proceeded with an imperial execution against the revolting villages and deployed troops in the country to quell the unrest. She examined the demands of the community, but considered most of them "audacious, worthy of punishment, evil", but waived the payments to be made, which had resulted from the abolition of serfdom.

The violent suppression did not ensure a long hold for the reign of Marianne von der Leyen, as the French Revolution invaded German territory in 1793. In May, the countess recognized her precarious situation and fled from the French revolutionary troops.

Moreover, the region fell into ever-deepening debt. The lavish wedding of the heir prince and the construction of the Philippsburg exacerbated the situation and placed greater burdens on the inhabitants.

In addition, disputes over forest and charcoal rights had existed since 1765, which reached their peak in the St. Ingbert forest dispute in 1789. The St. Ingbert commune sought support from other communities, and so 19 of the 38 communities in the region gathered for a meeting in which they collected their protest in 25 points of complaint. These were submitted to the Regent, where they found no hearing, so the protests continued.

In December, Marianne von der Leyen proceeded with an imperial execution against the revolting villages and deployed troops in the country to quell the unrest. She examined the demands of the community, but considered most of them "audacious, worthy of punishment, evil", but waived the payments to be made, which had resulted from the abolition of serfdom.

The violent suppression did not ensure a long hold for the reign of Marianne von der Leyen, as the French Revolution invaded German territory in 1793. In May, the countess recognized her precarious situation and fled from the French revolutionary troops.

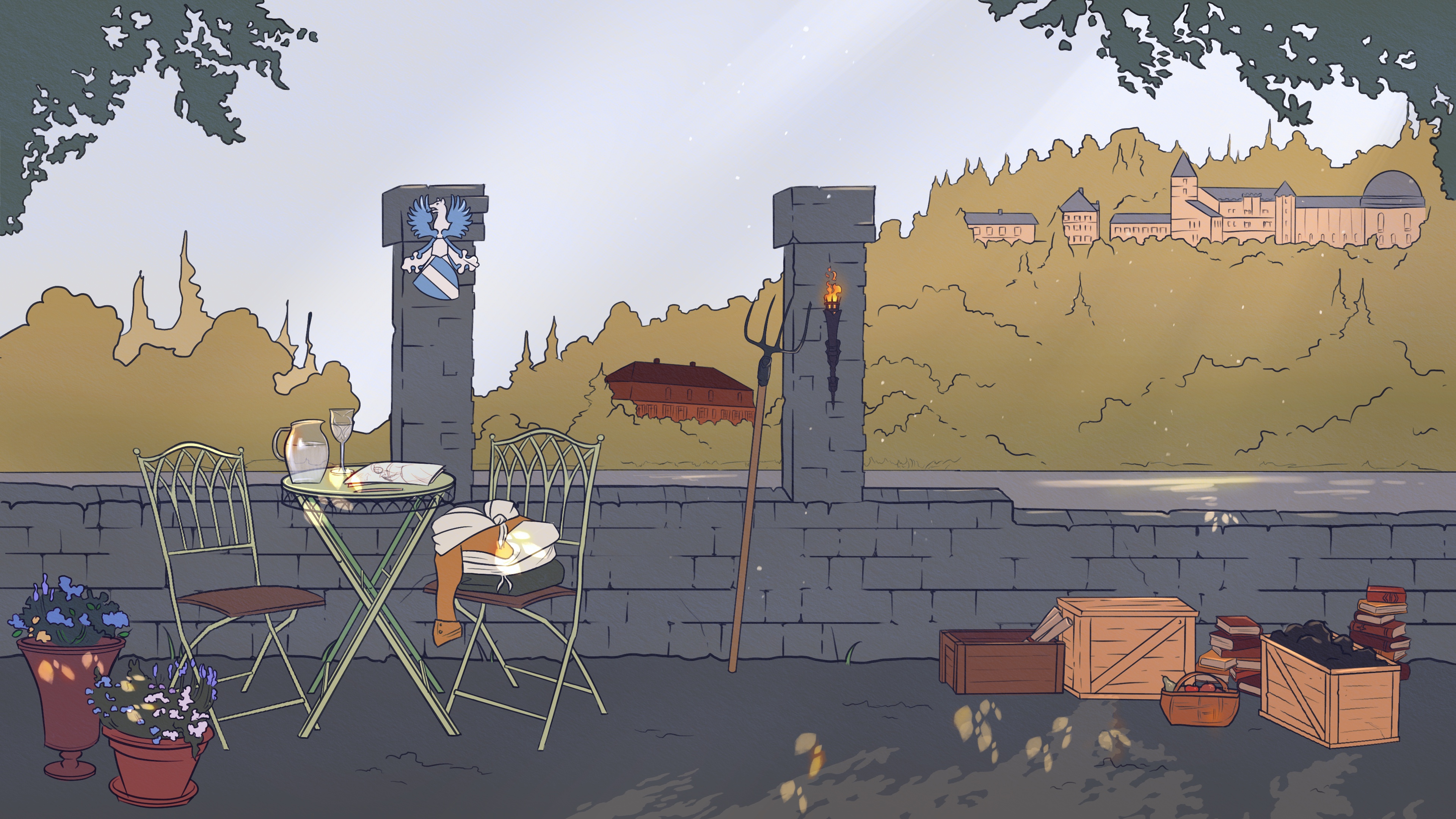

The "Journal of My Misfortunes"

As the French revolutionary troops approached, Marianne von der Leyen was already preparing to

flee. Initially, she stayed in the residence palace, but soon moved into other rooms, where she

kept a maid's dress in preparation.

On May 14, 1793, revolutionaries entered Blieskastel at last, intending to take her to Paris, but disguised as a maid, she managed to escape through a window. For over a week, she had to sneak through the villages of her county, with numerous residents helping her. She documented her escape in the "Journal of my Misfortunes", in which she described how she kept herself hidden. She begged residents to shelter her in their homes in a place where she would not be found. Among other things, she spent two nights in a wooden compartment in the attic of a house that was only accessible through a hatch, which was secured by pushing a wardrobe in front of it for safety.

In the end, Marianne von der Leyen's allies reached her, granting her a safe escape to Zweibrücken. Ultimately, she succeeded in crossing the French lines and found safety with the Prussian military.

She spent the next ten years in exile in Frankfurt am Main, where she died at the age of 60 from gout and a lung disease. Initially, she was buried in Heusenstamm, but her remains were reinterred next to those of her husband in Blieskastel in 1981.

On May 14, 1793, revolutionaries entered Blieskastel at last, intending to take her to Paris, but disguised as a maid, she managed to escape through a window. For over a week, she had to sneak through the villages of her county, with numerous residents helping her. She documented her escape in the "Journal of my Misfortunes", in which she described how she kept herself hidden. She begged residents to shelter her in their homes in a place where she would not be found. Among other things, she spent two nights in a wooden compartment in the attic of a house that was only accessible through a hatch, which was secured by pushing a wardrobe in front of it for safety.

In the end, Marianne von der Leyen's allies reached her, granting her a safe escape to Zweibrücken. Ultimately, she succeeded in crossing the French lines and found safety with the Prussian military.

She spent the next ten years in exile in Frankfurt am Main, where she died at the age of 60 from gout and a lung disease. Initially, she was buried in Heusenstamm, but her remains were reinterred next to those of her husband in Blieskastel in 1981.